Last Friday's IT meltdown was quite a ride. Picture this: thousands of corporate machines collectively fainting into the infamous blue arms of the Windows BSOD (Blue Screen of Death). For the very lucky few, it turned out to be a great excuse to take a well-deserved day off, while sys admins likely had to put in one if not a few all-nighters to reboot every machine one by one. But there were many more severe victims of this outage: lots of people got stuck because their flights were cancelled and even hospitals had to put surgeries and treatments on hold because the machines holding patient records were frozen.

Basically, we witnessed the first massive worldwide IT failure before we got GTA VI.

I am here today to dive into the Crowdstrike incident: from its technical cause to what I think is its deepest root, an oversight of fundamental development and integration standards, caused by a shareholder economy and a current tech market mostly focused on creating buzz over creating quality products.

Table of Contents

- Shareholder capitalism

- The post-pandemic tech market

- The Crowdstrike global IT outage

- Our current overreliance on Gen AI: last week's incident is one of many to come

Shareholder Capitalism

It's odd to be talking about economics, or so it feels, since I started this blog with the idea of discussing my journey in tech. But here we are, and I think that part of all this mess can be attributed to shareholder capitalism. As its name suggests, it's an economic model that prioritizes maximizing returns for a company's shareholders above other considerations. In this model, the primary goal of a corporation is to increase shareholder value, typically through strategies like maximizing profits, increasing stock prices, and distributing dividends.

Picture this: Tech bros chasing growth like it's the last slice of pizza. They're all about that "move fast and break things" life (I'm side-eyeing the Agile manifesto here 😏), hoping to hit the jackpot with sky-high stock prices. It's a non-stop party of mergers, acquisitions, and "disruptive innovation" (whatever that means, right?).

But here's the kicker – it's not all sunshine and IPOs. This obsession with pleasing shareholders can lead to some pretty whack decisions. We're talking short-term thinking, data privacy becoming more of a punchline than a priority, and employees feeling like their stock options are a rollercoaster they never signed up for.

Don't get me wrong, this model has given us some mind-blowing tech. But it's also served up a hefty side of ethical dilemmas and "oops, did we just create a monopoly?" moments. Look no further than the S&P500 or the NASDAQ. Both indexes are very dependent on the price of tech stocks, which after looking at the earnings of the tech giants with the biggest slices in these indexes, makes me wonder whether the share prices of these companies are actually realistic.

While shareholder capitalism has undoubtedly contributed to the rapid growth and innovation in the tech sector, it has also faced criticism for potentially neglecting other stakeholders such as employees, customers, and the broader community.

The post-COVID tech market: layoffs, outsourcing and cost-cutting

The relationship between shareholder capitalism and the tech market's growth post-COVID is a complex and fascinating one. When the pandemic hit, it created unique conditions that accelerated many existing trends in the tech industry, amplifying the effects of shareholder-driven decision-making.

Remote work technologies saw an unprecedented boom as companies worldwide were forced to adopt work-from-home policies. Firms like Zoom, Slack, and Microsoft (with Teams) experienced rapid growth, with their stock prices soaring. This growth was further fueled by shareholder expectations, pushing these companies to expand their services and features at a remarkable pace.

Similarly, the e-commerce sector experienced explosive growth as many of us shifted to online shopping, partially out of necessity, but also because staying home all day was insanely boring. Amazon and Shopify were among the biggest beneficiaries, with their stock prices climbing significantly. Shareholder pressure in this sector led to aggressive expansion strategies and increased investment in logistics and delivery infrastructure. At the same time, cloud computing was another area that saw substantial growth, as businesses rushed to digitalize their operations.

This period of rapid growth led to concerns about a potential tech bubble, with some drawing parallels to the dot-com boom. The rise of SPACs and inflated valuations of tech-adjacent companies illustrated how shareholder enthusiasm could sometimes outpace business fundamentals.

For those in tech (me included), it was a sweet paradise. Everyone was hiring and working from home was very widespread.

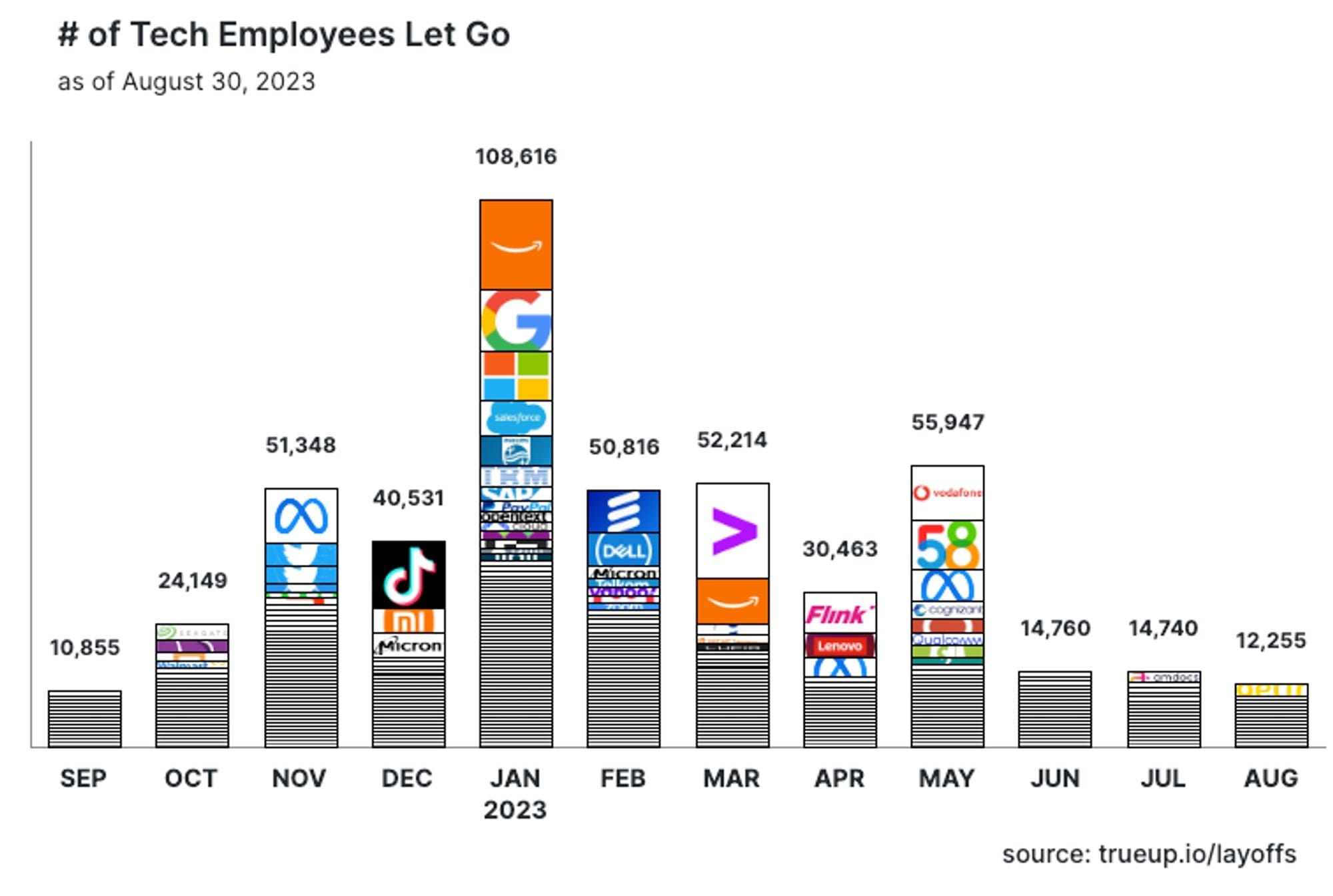

But that didn't last long. The tech sector landscape changed significantly after the initial pandemic boom, with the post-pandemic period marked by widespread layoffs in the tech industry. This shift was driven by a combination of factors that emerged as the world began to recover from the immediate effects of COVID-19: an economic slowdown and a spike in interest rates.

The latter made borrowing more expensive and reduced the value of future earnings, particularly impacting high-growth tech companies that had been relying on cheap capital.

Many tech companies found themselves overstaffed due to the aggressive hiring of the pandemic. They had anticipated continued rapid growth, but when this growth slowed, they were left with unsustainable workforce sizes. This overcorrection of pandemic hiring became a primary driver for layoffs.

Notable layoffs occurred at major tech companies including Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Twitter (now X), among others. These weren't minor adjustments but often involved thousands of employees, signalling a significant shift in the industry's approach to workforce management.

Another company that also went through a major round of layoffs was, as you may imagine by now, Crowdstrike. Although the figures for their round of layoffs was not as high as other tech companies, at about 200, some digging online points to a higher number of people affected, disguised as PIPs or RTO firings.

Additionally, advancements in automation and AI technologies made some jobs redundant, or that's what some companies are claiming (I am not sure of the veracity of this one), further contributing to job cuts.

Beyond layoffs, another common tool that big tech has used to cut costs is by outsourcing workloads to offshore teams. This is not a problem per se, but believing that you can pay someone 2$ an hour yet get high-quality and thoroughly tested code is naive, to say the least. This has been again very commonly done in the last two years as a way for big tech to pump their stock price.

The Crowdstrike IT outage

Now that we have gone through some context, it does make quite some sense that the Crowdstrike incident was bound to happen. Approximately 8.5 million Windows machines were affected by a corrupted update of Crowdstrike Falcon, an "AI-powered" security software that operates at the kernel level of a device.

Reports suggest that Linux servers encountered a comparable problem with CrowdStrike earlier this year, specifically in April. This incident has led some experts in the field to point out what they perceive as a significant lapse in quality assurance ( surprise surprise) that both CrowdStrike and Microsoft fell short in properly addressing this issue.

I'll leave the technicalities behind Falcon's update fiasco for another time, but for those curious, I found this video by former Microsoft engineer Dave's Garage to explain the matter quite clearly.

The corrupted update crashed millions of computers because of a configuration file, then Windows did what it should when a critical driver crashes at boot time: it stopped working and showed the "blue screen of death".

This event is not a standalone occurrence. Earlier in the year, Crowdstrike was involved in comparable problems affecting Linux systems, particularly those based on Debian and Rocky distributions. However, this incident received less attention due to its more limited impact, compared to the recent Windows disruption. In both cases - the Linux incident and the Windows outage - inadequate testing appears to have been a key factor contributing to the problems.

Something as simple as integration testing or a canary release would have prevented the frenzy of last month.

These incidents raise questions about broader trends in the tech industry today. They seem to highlight several concerning patterns: a potential decline in comprehensive end-to-end testing practices, accelerated development schedules that may compromise thoroughness, and a shift in priorities towards generating buzz and quick profits rather than ensuring the delivery of high-quality software products.

I don't even blame the engineers. Based on information from various articles and forum discussions, it seems that several strategic decisions made by Crowdstrike may have contributed to the recent quality assurance shortcomings. These decisions reportedly include a round of layoffs, a shift towards outsourcing to less expensive remote teams, and a push to incorporate AI technology through their Charlotte AI initiative. These factors potentially played a significant role in the decline of QA effectiveness this year.

And there is the next point that I want to get into...

Not everything needs an AI

Going back to the 1960s, we know humans are suckers for computers that pretend to be thinking machines, even when they’re doing nothing of the sort. The exponential progress the deep learning and NLP fields have seen in the last few years have been very sound and have changed the way people interact with technology quite significantly.

The truth is, no matter how much OpenAI, Google, and the rest of Silicon Valley's elite try to sell the idea that generative AI is revolutionizing digital technology, their fantasy is getting harder to sustain. Yet, the hype around large language models (LLMs) has swept up many companies, making them desperate to have their own AI. Now, it seems like everyone and their grandma is rolling out an LLM, which is usually just a wrapper around ChatGPT3.5 or ChatGPT-4.

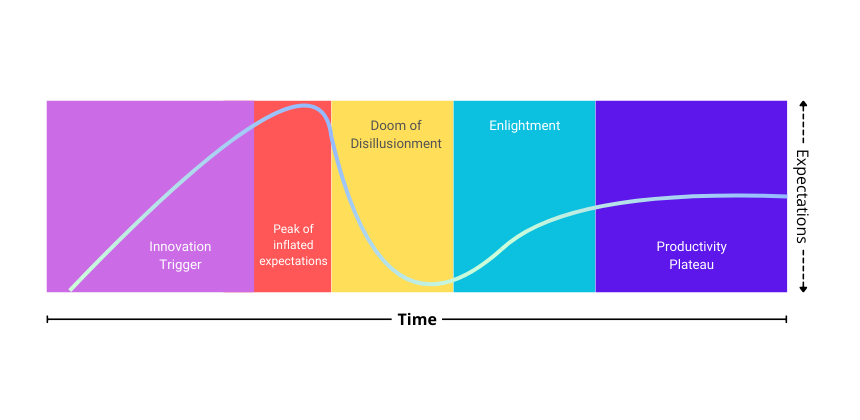

As happens with most hyped technologies, language models are going through a maturity and adoption process that can be described by five stages in a Gartner cycle, shown in the illustration below:

It could be argued that we're currently in the second phase of the Gartner Hype Cycle regarding Large Language Models (LLMs). There's a growing realization that LLMs may not be the direct path to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) as initially hoped, leading us to stage three of the cycle with disillusionment on the horizon. However, this realization doesn't diminish the potential for significant advancements in other areas of machine intelligence, including complex systems and non-human-centric approaches.

The heightened enthusiasm surrounding AI has led many companies to jump on the bandwagon, seeking increased funding and profits. However, the actual adoption and practical implementation of these technologies often lag behind the hype. A significant challenge lies in the resource-intensive nature of LLMs, both in terms of training and hosting. The energy requirements for widespread adoption might even surpass our current grid capabilities.

The tech industry now faces a critical question: how long will companies continue to invest enormous sums into maintaining this inflated bubble of AI hype? Observing a CEO tallying AI mentions during a presentation suggests that some may already be stretching their resources thin, relying more on buzzwords than substantial technological progress.